for the roses Had the look of flowers that are looked at.

I was stressing and he was fuming as we hurried to the cab waiting for us downstairs at four am. We had slept two hours, woke up from the insistent sound of a back-up alarm set on my phone, fifteen minutes before we had to leave. Why did I set it to ring so late? I was waiting for lighting to strike from the thundercloud beside me. The sky was clear over London, glowing at this hour as if by itself, neither ray nor sun being visible. The stones of the city beneath were luminous and shadeless, the buildings flat like technical drawings, appearing for a moment before daybreak in their ideal, Platonic forms. It was a gorgeous cab ride, intimating perfection. Lightning would strike later, at the airport: I was the offending cloud, stress being the more charged state. Reconciliation came at the Le Labo counter; the price was incredible, we bought one big bottle each and entertained each other all the way to Copenhagen by smelling our scented wrists.

Two things, it seems, are required for me to find a trip worth diarising: vexation and nudity. This is of course only true ceteris paribus, all else being equal. Things are a bit different when one travels alone, to mention one important factor not held constant across the three travel diaries I’ve hitherto published. Solo travelling is a melancholic pursuit, unless you’re a backpacker content to play drinking games in a hostel. The thirty-something man sitting next to us at a Czech bar in Malmö, the one wearing chic Saint Laurent sun specs and ugly beige cargo shorts (let’s not speak about his ghastly trainers), who I thought was a Swede waiting for his mate picked up his phone and proved me wrong by speaking in a Slav-accented English about some geographically and culturally distant business matter. The way he drank his beer, looking out, sunward, into the street, would’ve instantly given him away to a more astute observer as a lone tourist forced, by the gregarious foreign chatter around him, to contemplate his unhappy individuality. One would rather be Robinson Crusoe on a desert island or me, two years ago, eating a schnitzel in an empty restaurant in covid-era Hamburg, than to sit there, having paid all this money and travelled all this way, with one’s expensive sun specs, only to be frozen out of humanity.

No, this time I wasn’t travelling solo. Having a companion does away with certain indignities, but it doesn’t grant you access to a place. You can take your banal pictures of the sights or read your guidebook, but that gets you no further than an iconic or lexical acquaintance – you might as well have stayed at home. The way in is through people. ‘“No” one says to beauty’, wrote Virginia Woolf, ‘as one rebukes an importunate dog, “down down; let me look at you through the eyes of human beings.”’

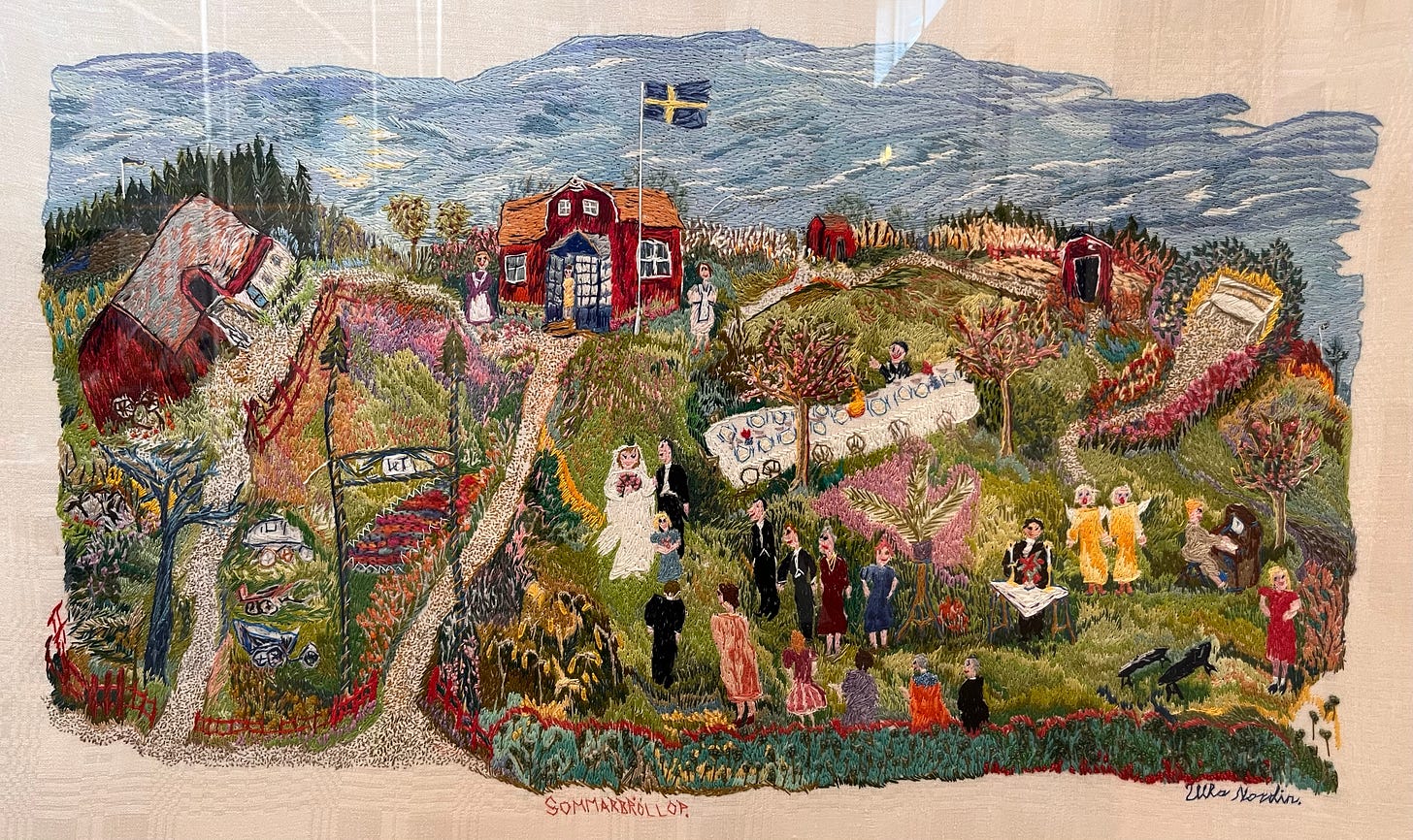

Intimation of perfection: an early morning swim alone in a still lake. An experience of purity, at once full and empty, being and nothing; an appearance of a quiescence of appearance, a brief moment of eternity, a dialectical standstill.1 But after swimming in a thousand lakes, stopping for a dip every fifteen minutes on our drive up to the little town in Småland, we found ourselves being treated to a tour at a gallery opening. Here, finally, were some human beings. ‘This was the house of Julius Lehmann’ we were told, a Berlin carpenter specialising in marquetry who came to Sweden before the Second World War. His son Rolf made huge panels for the luxurious ocean liners of the Sverige-Amerika line. We, uninvited, were given lunch – a piece of leavened bread topped with sesame paste, some leaves and, strangely, croutons. ‘Kaka på kaka’ one says in Swedish, ‘cake on cake’, too much of a good thing. A man we chit-chatted to about London turned out to be a former director at a prestigious literary institution in the capital. ‘The Stockholm cultural elite’ was here, giggling at a joke about the far right, drinking alcohol-free beer while standing in slack contrapposti. Many were wearing socks and Birkenstocks. It was a warm day. A fellowship recipient said the doubts he had had about the value of his work as a full-time artist with two small children had been dispelled by the recognition he just received. It seemed a Scandinavian problem – having doubts about the value of one’s work. I think I read about it somewhere in Knausgård: a mildly successful artist raising several children in relative comfort has doubts, wants to prove himself. In anglophone countries, the problem of aesthetic merit has largely been solved by swapping it for moral judgement. Where there used to be poseurs, styling themselves like rive gauche intellectuals or Che Guevara, they’re now moralists reciting litanies of identities. I empathise. It’s easier to labour for a recognised cause, for something apparently useful, than it is to do marquetry as a dad. But I’m glad this man’s work was able to speak for itself, that there’s still space for people to be artists and craftsmen rather than activists.

We had been generously received, the weather was brilliant. Nevertheless, vexation: not at uncouth tourists on a WizzAir flight to Málaga but at the fat man menacingly circling the bag we left on the beach, the group of young men loudly chanting in Arabic at ten pm. Flies in the ointment no journalist would mention in their travel piece on Sweden. ‘When will it stop’ said an older gentleman in a sauna in Malmö about a shooting the night before, the 155th this year so far. Far more than an attractive image was being spoilt. At the open-air bathhouse we were told to buy a padlock as there had been a spate of thefts recently. Anecdotal inconveniences, statistical trends. Nothing of ours was, in the end, stolen; we weren’t shot. We saw King Carl Gustav XVI and Queen Silvia parade for a diamond jubilee visit from the train station to the main square. The police officers were wearing short-sleeved light-blue shirts. Their barricade tape was in the colours of the Swedish flag. ‘He’s not the sharpest tool’ said another sauna patron of the King. ‘None of them are, I mean our rulers’ said another. Sweating men were talking about the covert corruption within the Social Democratic Party, all the professional posts they’ve given to their mates over their decades in power, the government contracts they handed out to loyalists. Ilija Batljan was mentioned, a former regional representative of the party who moved from politics to real estate and convinced local authorities to sell municipal buildings – schools, nursing homes, sport halls – to his company, Samhällsbyggnadsbolaget (SBB), in return for long-term leases. Having made those purchases using borrowed money, SBB is now in the midst of a debt-crisis due to higher interest rates, putting its taxpayer-funded property portfolio at risk of acquisition by foreign wealth funds. The company has become so big that its present woes have, I’m told, contributed to the decline of the Swedish krona. ‘It ain’t worth shit’ we heard someone grumble by the hot stones.

The drive back down to Malmö, after our stay in Småland, felt much shorter than the drive up. I’m always taken by this experience of Bergsonian durée while motoring, the way the experience of time stretches and compacts. Travelling, I mean the part where one is in transit, is the most reliably boring activity in my life. Perhaps the highs of excitement it also induces have to be balanced out with some dreary lows (if Schopenhauer had been a statistician, he’d love regression to the mean). I’m sympathetic to the travel Grinch du jour, Agnes Callard. Modern tourism is rotten, I agree, but the dreariness of travel can be virtually eliminated with the right itinerary (a stop at least once an hour) and means of locomotion (a pearl-white Volvo XC40 with an Orrefors crystal gear selector). Frequent stops make up somewhat for the rapid change of scenery that Kafka noted separate modern travel from the ‘pastoral form of thinking’ evident in Goethe’s accounts of his mail-coach trips. ‘The slow changes of the region, develop more simply and can be followed much more easily even by one who does not know those parts of the country.’ Modern travel is essentially characterised by irreducible and disorienting discontinuities – caveat lector!

I wanted to go swim in the sound as soon as we arrived. On the beach a green wooden building connected to the land by a long pier rose on pillars from the water. There was a light drizzle. We paid eighty kronor each to enter plus fifty kronor for the padlock. Ribersborgs Kallbadhus: this was the site of those hot conversations above. I’ve visited the ruins of Diocletian’s Baths in Rome, seen the exposed heating system for a caldarium in Pompeii, but it’s only in a Swedish bathhouse that I have experienced something of what these places must have been like to visit. An open-air bath, or ‘kallbadhus’ (lit. ‘cold bathing house’) is a mix of gym, spa, and social club. As the website for Ribersborg’s bath states, swimming costumes are allowed, ‘but 99% of our visitors bathe naked’. An English tourist walked around briefly in lycra boxers before slipping them off to join his girlfriend in one of the mixed saunas. ‘You live in London but you’ve found paradise here in Malmö’ a regular said to me. He was right. You cannot bring a phone in the water or the sauna. It would be, I think, criminal to photograph someone naked without their permission. It’s a space completely free of technological distractions. At most people will read books in the hot-air baths. I found a copy of Patrick Modiano’s Un Pedigree, in French, in the magazine rack – I’d have reacted with a heart-eyes emoji if I could. It’s difficult to read, however, as people like to talk, though there is one quiet sauna, with a view of the sound and the pontoon deck anchored in the water where naked men and women sun themselves. Forget the Sistine Chapel, this was one of the most civilised rooms I’ve ever visited.

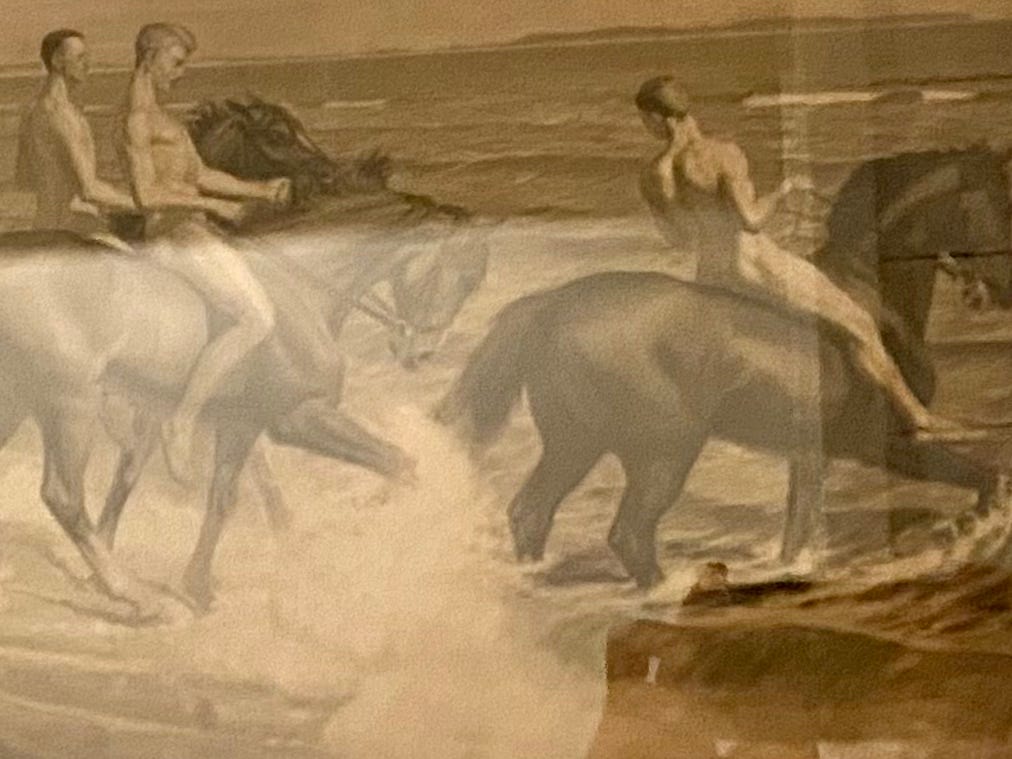

In the bathhouse, one is shut out from the symbolic world of status. There are no sickly layers of maquillage and false lashes, no logos on display, no expensive watches or Versace slippers. Here you reveal yourself as you are au naturel. Nature, of course, has her own hierarchies, and there’s a whole image world of the body no less unforgiving than the symbolic world of commerce. Are nature’s distinctions easier to accept? Or is everything that appears natural merely a successful naturalisation? Take this tall slim deeply bronzed ephebe with a gorgeous curl to his upper lip, not just strikingly beautiful but also shockingly well endowed. He was there with an older man, what I presume to be an uncle. They spoke of a disputed jetty that had soured the summer of a relative; about the inheritance of the youth, how it will be diluted among his siblings; the beautiful plans for the summer house his parents had that were now but a wistful sigh. This boy was, I suspect, the product of some rich man, a while back, taking a beautiful woman for his wife. Genes can and have been bought for quite some time. But wasn’t there, upon further thought, something vulgar in his appearance, something evoking a world of lip fillers and breast implants – the deep tan, the satyric schlong, his front-combed straight hair à la Justin Bieber? Just as the beauty of a Greek column was inseparable from its function of bearing the roof of the temple, so the beauty of a youth was inseparable from his achievements in games and battles. The young man was no ephebe but a Dorian Gray, the slightly grotesque epitome of art for art’s sake (aestheticism is always a tad grotesque). As to nature, what we find exemplary in it would often be more accurately described as ‘classical’; as the great religions teach us, it’s artifice all the way down.

In the afternoon, a young man walks in to a bookshop and asks the shop owner if they have any Rilke. My ears pricked up immediately. Have I ever witnessed this before? A young man asking for Rilke? Never. The shopkeeper points to the section marked ‘lyrik’ – rarely does one group lyric and epic poetry together in Sweden. He looks through the shelves for his inquiring customer, says they have a scholarly book on Rilke, if that’s what he meant? No, he meant a book of poems, primary not secondary lit. The book is found. ‘Here’s a volume by him. Or is it a she?’ The young man says, with an air of deprecation at such ignorance, that Rilke’s a ‘he’. ‘I’m always thrown off by men named Maria’ answered the shopkeeper.

In the boxes of discounted books outside, which featured recognisable, even eminent titles quite unlike similar displays in London – surely no one could think to put a rebate on Kafka, and yet here was the famous letter he wrote to his father printed and bound in a fine Taschenbuch – in these boxes a title caught my eye: flanör i Malmö, the first word entirely in minuscules for some reason.

‘Flâneurs are a metropolitan phenomenon – people with a similar disposition are called “tramps” in the countryside. The encyclopaedic definition suggests the flâneur is a slighlty asocial type. Perhaps the texts and drawings in this book make the same impression, but they should also prove that flanning is not always unproductive.’

It staggers belief to think of Malmö, a town of some 300,000, as a metropolis, yet many Swedes will insist on distinguishing it with the designation ‘storstad’ – big city. The book was a collection of short pieces by two journalists published in 1979. There’s one on Ribersborg’s bathhouse where our flâneurs observe that ‘naked men, who just slapped each other on the back, were doing pushups’. Apparently the custom for yachts to anchor in view of the pontoon is at least a few decades old, though the authors complain of a dwindling number of female bathers to ogle from one’s deck. Too much space is given to interpreting the irritating presence of a swan. A good piece of flânerie, if it has to be written down, should be like a watercolour by Constantin Guys, the ‘painter of modern life’ as Baudelaire famously dubbed him: a snapshot of the ever-changing human scene.2 A swan’s eternal, it’ll outlive the bathhouse and its bathers. One must look at the world through the eyes of human beings.

As we returned to the hotel to pick up our bags, about to set off for the airport, we receive news that our flight is cancelled. The earliest replacement flight is twenty-three hours away. We must stay another night, happy to be gifted a stretch of unaccounted for time. Between the plans we had until departure and the routines we’d go back to on arrival was a night and a day which hadn’t yet been defined in any way, which had until recently not existed. Here’s perhaps another intimation of perfection, a duration suspended into which we plunged, once again, naked, bathing in the clear, eternal, slightly salty water of Öresund.

My personal canon of ‘perfect’ moments includes, apart from four am cab rides and morning swims, a glass of dry white wine whetting my appetite before a meal, prinks, the first night of a trip at some intermediate location, the first few nights in a new house spent living among unpacked boxes, the half-conscious moments before I wake up. I’m not sure what these things have in common. Take the wine: it has an inverted effect, it doesn’t sate but makes the appetite grow stronger. I think I fancy myself being able to just sip this cold golden wine and perhaps nibble on a tarallo forever without ever feeling full, eternally anticipating the delicious meal to follow. In practice this wouldn’t work, of course, but like a good Epicurean I know that maximal pleasure lies in judicious moderation. Take a sip or two and contemplate the implied conclusion to this hinted logic.

Is this a piece of flânerie? It couldn’t be, for I wasn’t alone, I was abroad, vexed and nude, states antithetical to flanning.