One evening, in the horizontal light, soft and colourful, with an acute sense of my depravity, having just published a piece with the phrase ‘satyric schlong’ alongside observations from a nudist bathhouse in Sweden, I sought refuge in the pages of Kafka’s diaries, that ‘twenty-first century Dante.’ I open a page at random. ‘2 beautiful Swedish boys with long legs, which are so formed and taut that one could really only run one’s tongue along them.’ Okay. On the previous page: ‘8 July (1912) … Everyone except me without swimming trunks. Beautiful freedom. In the park, reading room, etc. one gets to see pretty fat little feet.’ Right. I’m sure there’s a circle in hell for this. What’s going on?

(Let no coincidence go unrecorded. That may sound like the beginning of a conspiracy, and isn’t it just, ever since Baudelaire or whenever, that literature has been a conspiracy against modern disenchantment? Coincidences and correspondences, the language of flowers and mute things. Some go too far, get tangled in invisible links. I’m being selective.)

In July 1912 Kafka went to Kuranstalt Jungborn, a sanatorium and spa near Stapelburg. This was a few years before his tubercular diagnosis. He listened to an evening lecture on clothes. Rudolf Just, the author, publisher and leader of the Kuranstalt, advocated, I suspect, wearing none, for health’s sake. ‘I’m known as the man with the swimming trunks,’ Kafka notes. The naturopathy taught at this place was cranky. ‘After a certain exercise the genitals will grow.’ Was Kafka self-conscious about the size of his Schlange? Or did he want to hide his circumcision? I ask this of a man who often felt himself to be a bug.

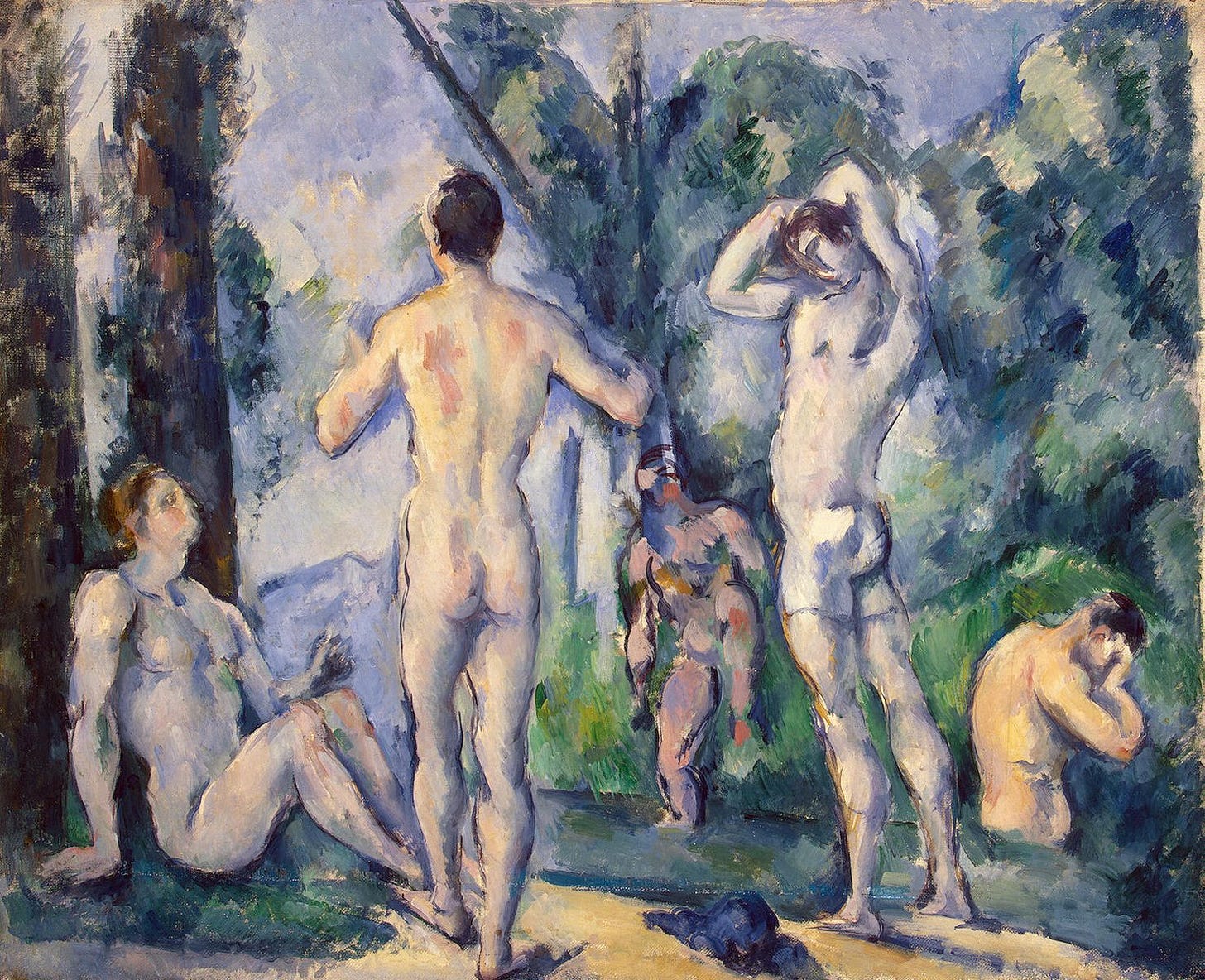

When nudity is voluntary, as one hopes it would always be, people are inclined to self-select. A nudist enclave tends to attract the shameless, usually old, and those with something to show. I wanted to add ‘the voyeuristic,’ but nudism implies a level of participation that seems incompatible with voyeurism. Those with an inferiority complex tend to stay away, or like Kafka, attend clothed.

Another coincidence: it’s the seventieth anniversary of Ingmar Bergman’s Sommaren med Monika (1953), a film that became controversial abroad for ‘its frank depiction of nudity.’ America had the Puritans and Britain had Queen Victoria covering sculpted genitals with fig leaves. (Did I mention my favourite ice cream flavour this season is fig leaf?) The nudity in Monika is of course, by our pornographic standards, tame. If anyone’s shocked by the sight of Michelangelo’s David today it’ll be for the modesty of its member. The classical sensibility, otherwise so remarkably resilient, has a blind spot around the crotch.

Despite porn, nudity still has the power to shock and embarrass. As Foucault observed, we’re not as liberated as we think we are. The men at the Highgate Men’s Pond, formerly with a nude sunning deck, both younger and older, who wriggle out of their swimming trunks while wrapped in towels reassert an Abrahamic conviction in man’s fallenness. Adam and Eve had been naked before God covered them up with fig leaves as punishment. I now understand why someone described a nudist bathhouse to me as ‘paradise.’ And of course, it’s difficult to think of Kafka daring to act out Eden on earth, though he taunted himself by observing it – a theological voyeur.